RBA starts the year off with a rate hike

By Dr Shane Oliver – Head of Investment Strategy and Economics and Chief Economist, AMP Capital | 3 Feb 2026

Key points

- The RBA hiked its cash rate by 0.25% to 3.85% as widely expected in response to inflation running above target.

- Its commentary was cautious and hawkish with inflation now expected to stay above target for longer even with assumptions for two more rate hikes and the stronger $A.

- We thought it was a close call and leaned to a hold. But having hiked we expect the RBA to hold for the remainder of the year as we see underlying inflation as having peaked in the September quarter and falling back to target.

- Valid concerns about capacity constraints though are likely to keep the risk of a further rate hike high.

- The best thing government can do to help alleviate this is to lower the level of public spending.

Introduction

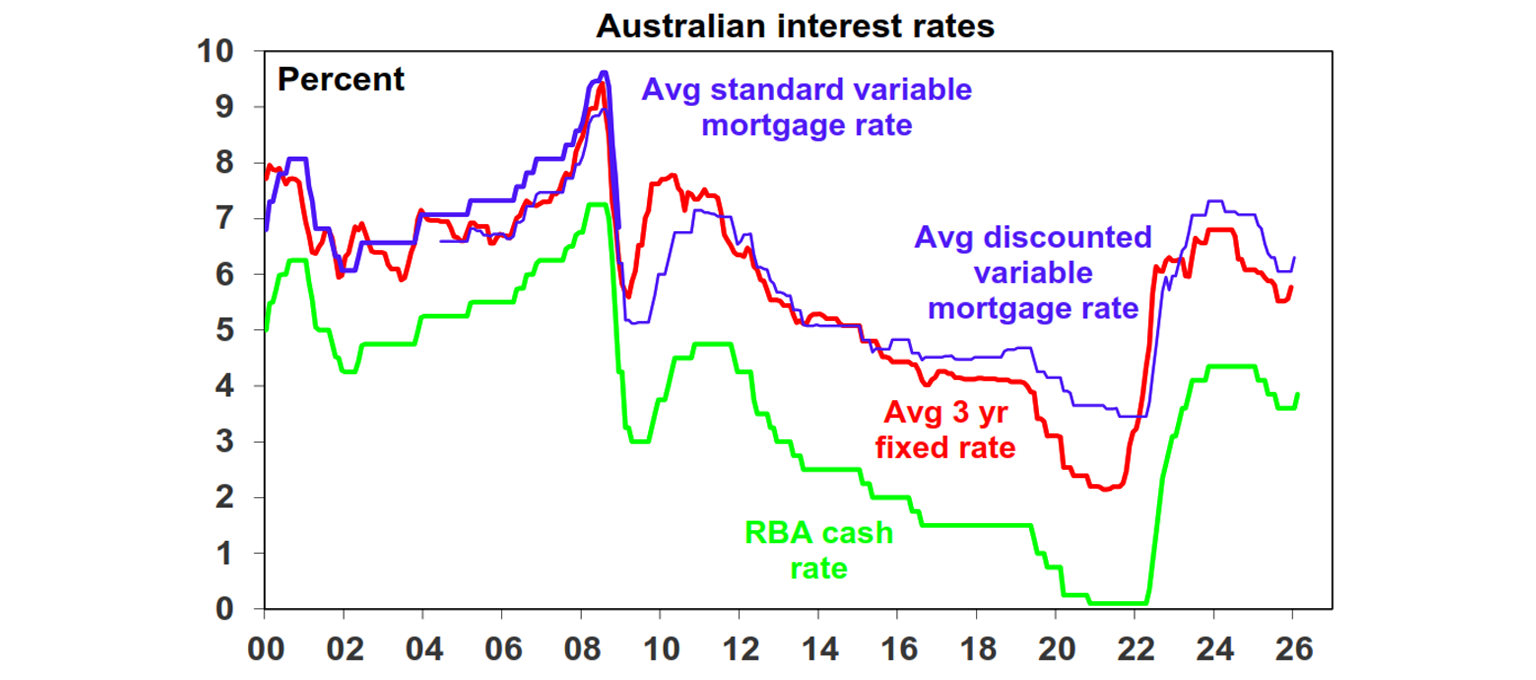

The RBA’s decision to hike rates to 3.85% was no surprise with it being about 70% factored in by the money market and 22 of the 28 economists surveyed by Bloomberg expecting a hike. We thought that the RBA should and (wrongly as it turned) thought it would hold but we also saw it as a very close call. The decision means that the RBA has already reversed one of the only three rate cuts we saw last year, which of course followed 13 rate hikes seen in 2022 and 2023. Once passed on to mortgage holders it will leave mortgage rates around levels prevailing 13 years ago. Of course, it should also mean a slight rise in bank deposit rates.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

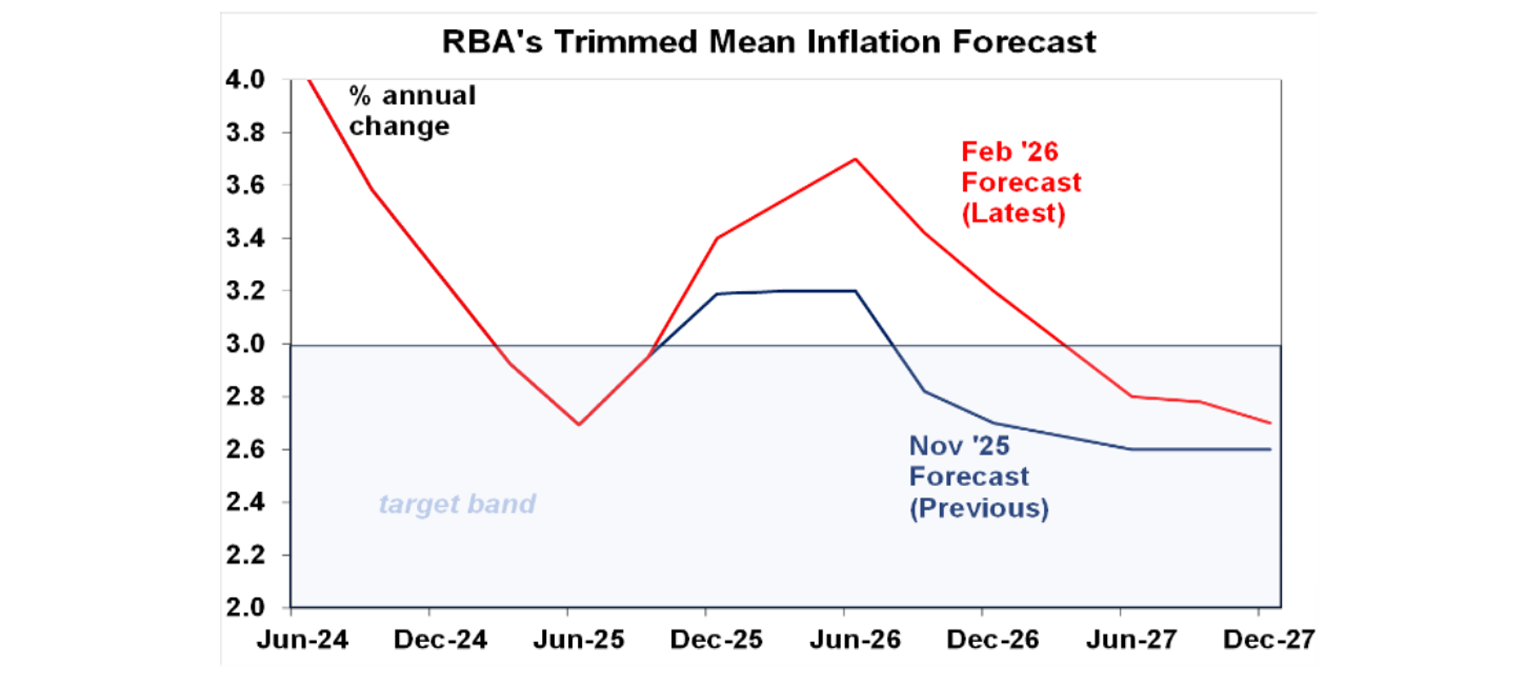

The decision to hike largely reflected the increase in annual inflation through the second half last year with quarterly trimmed mean (or underlying) inflation rising to 3.4%yoy and monthly trimmed mean inflation at 3.3%yoy, which is well above the 2-3% inflation target and was above the RBA’s forecast for 3.2%yoy. This has led the RBA to conclude that the economy has less spare capacity than it previously thought.

Governor Bullock’s press conference comments basically reinforced these concerns and indicated caution regarding the outlook leaving the door wide open for further interest rate hikes if needed.

Consistent with its decision to hike the RBA now sees inflation staying above target for longer, despite assuming a higher $A and two more rate hikes the RBA now sees underlying inflation staying higher for longer and not really getting back to the midpoint of the inflation target until June 2028. This reflects its revised assessment that the economy has more capacity pressures than previously assessed – compared to say back in August last year when it saw inflation around target even with two or three more cuts! Of course, as the lagged impact of the forecast growth slowdown flows through inflation could conceivably fall below target in 2028-29 but that’s a long way off.

Source: RBA, AMP

We expect the RBA to leave rates on hold

There is an old saying that rate hikes are like cockroaches – if you see one there is likely to be another! However, we lean a bit more optimistic and expect this to be a case of one and done:

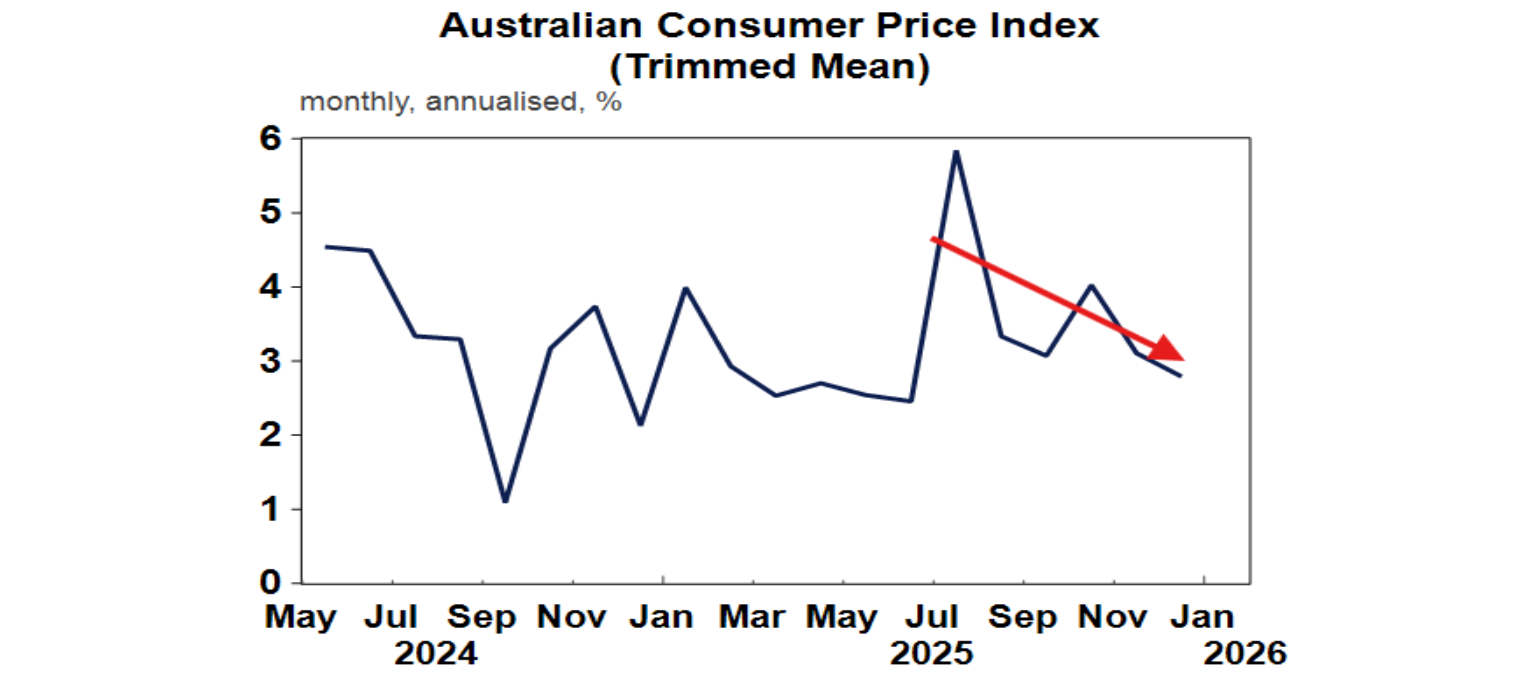

- Monthly trimmed mean inflation has progressively trended lower from 0.47%mom in July to 0.23%mom in December and slowed from 1%qoq in the September quarter to 0.9%qoq in the December quarter.

Source: Macrobond, AMP

- We still expect underlying inflation to fall back to target this year.

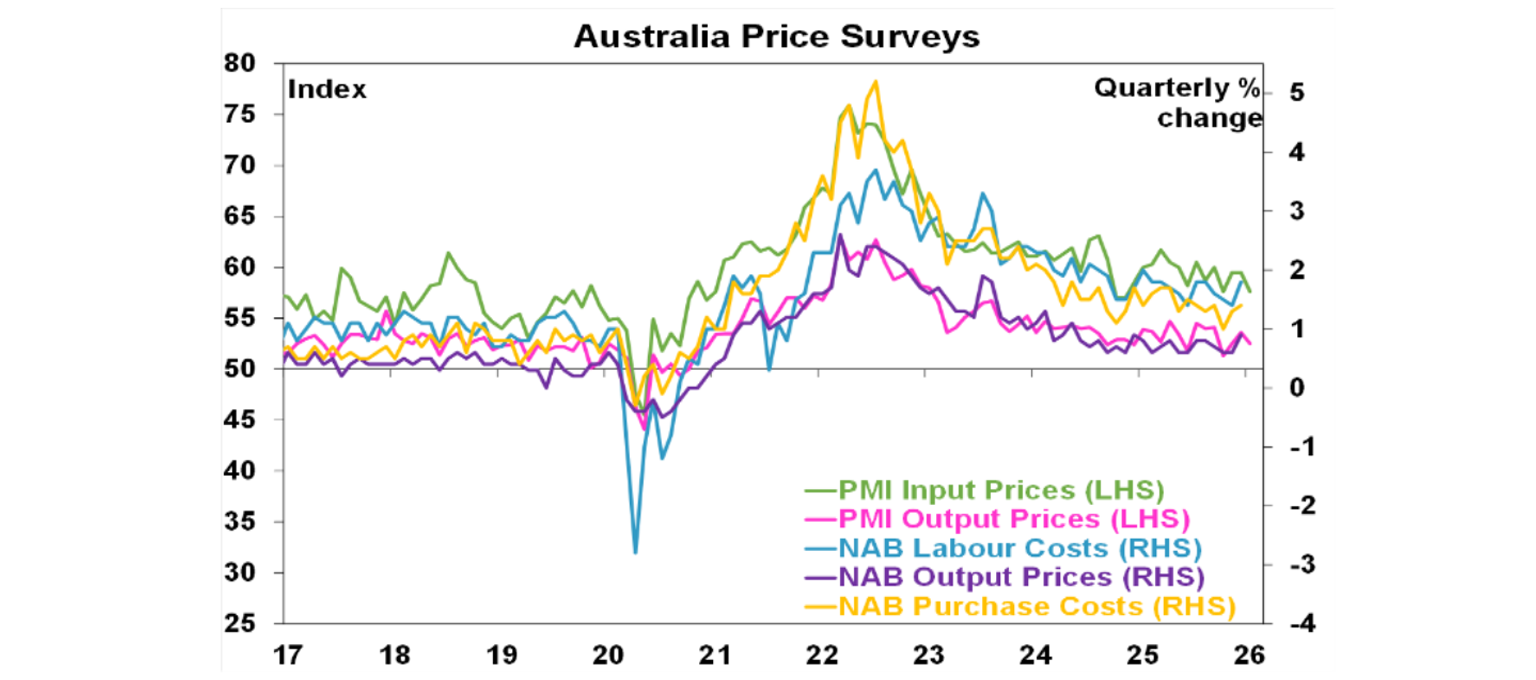

- Business surveys show output price indicators around levels consistent with the inflation target – see the pink & purple lines in the next chart.

Source: NAB, Bloomberg, AMP

- Consumer spending is likely to take a hit as we have swung quickly from rate cuts to hikes as mortgage stress likely remains high. For mortgage holders – who are far more responsive in their spending decisions to changes in their disposable income than outright homeowners – the RBA’s 0.25% hike will mean that their interest payments will start going back up again. For someone with a $660,000 average new mortgage this will mean roughly an extra $110 in interest payments a month or an extra $1300 a year. This will likely dent spending, particularly as expectations will now be for more hikes. Sure those relying on bank deposits will be better off but household debt in Australia is almost double the value of household bank deposits.

- The rise in the Australian dollar is a defacto monetary tightening that will help lower imported inflation.

That said, the risks are still skewed on the upside for the cash rate if domestic demand growth continues to strengthen adding to concerns about the economy bumping into capacity constraints and if inflation does not fall as we expect. On balance we expect to see the cash rate remain at 3.85% for the remainder of the year, and we see money market expectations for two more rate hikes as being a bit too much.

The key to watch for what happens next year will be the monthly inflation data. Another move in March seems unlikely given that the RBA has just moved but March quarter CPI data to be released in late April, ahead of the RBA’s May meeting will likely be key. If it shows a further cooling in trimmed mean inflation as we expect then the RBA will likely hold.

How can government take pressure off inflation?

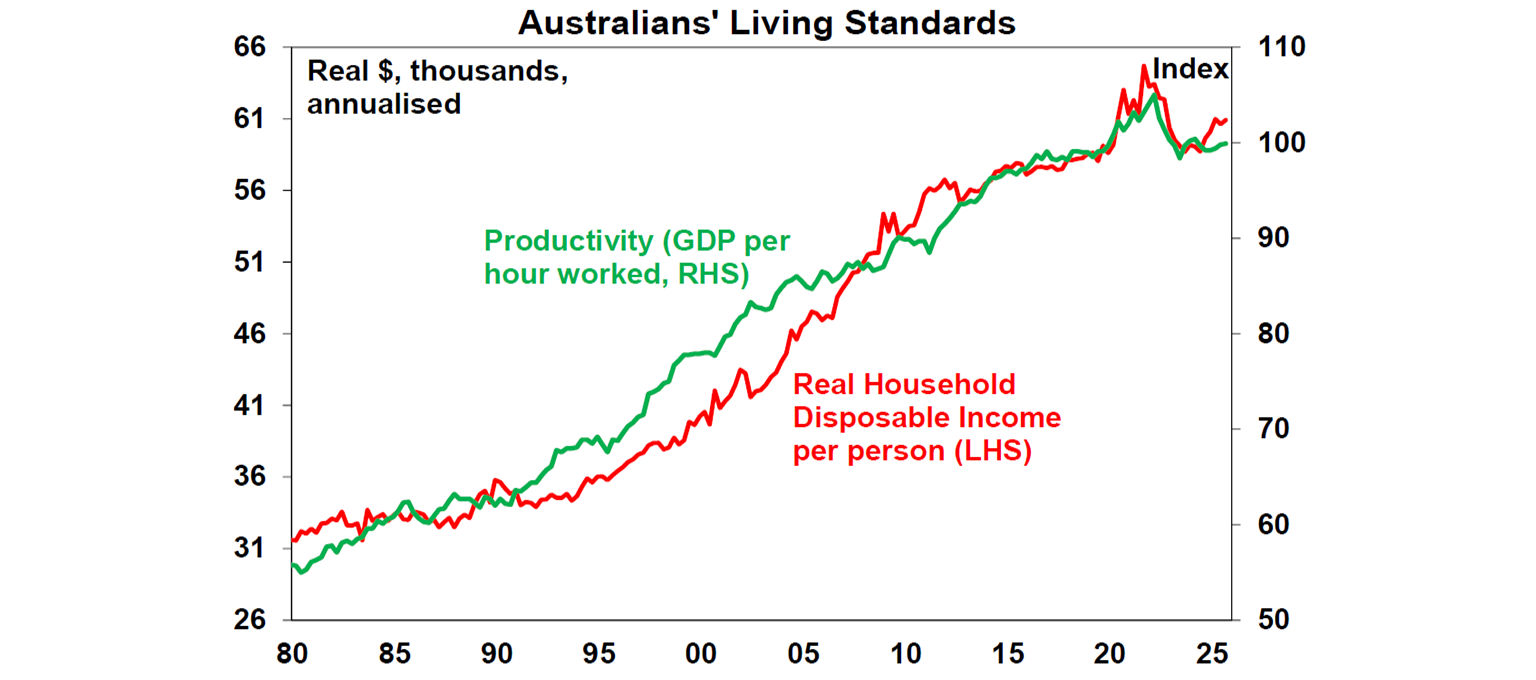

Whether it was a hold or a hike, inflation has proven more sticky than expected a year ago. Pressure to deal with this has largely fallen on the RBA but Australian governments could make life a lot easier for it. Government is contributing to the strength in inflation in Australia in two ways. First, prices for items administered by government or indexed are rising around 6%yoy, well above the 2.9%yoy price rises for items in the market sector of the economy. So governments should be looking for ways to lower this.

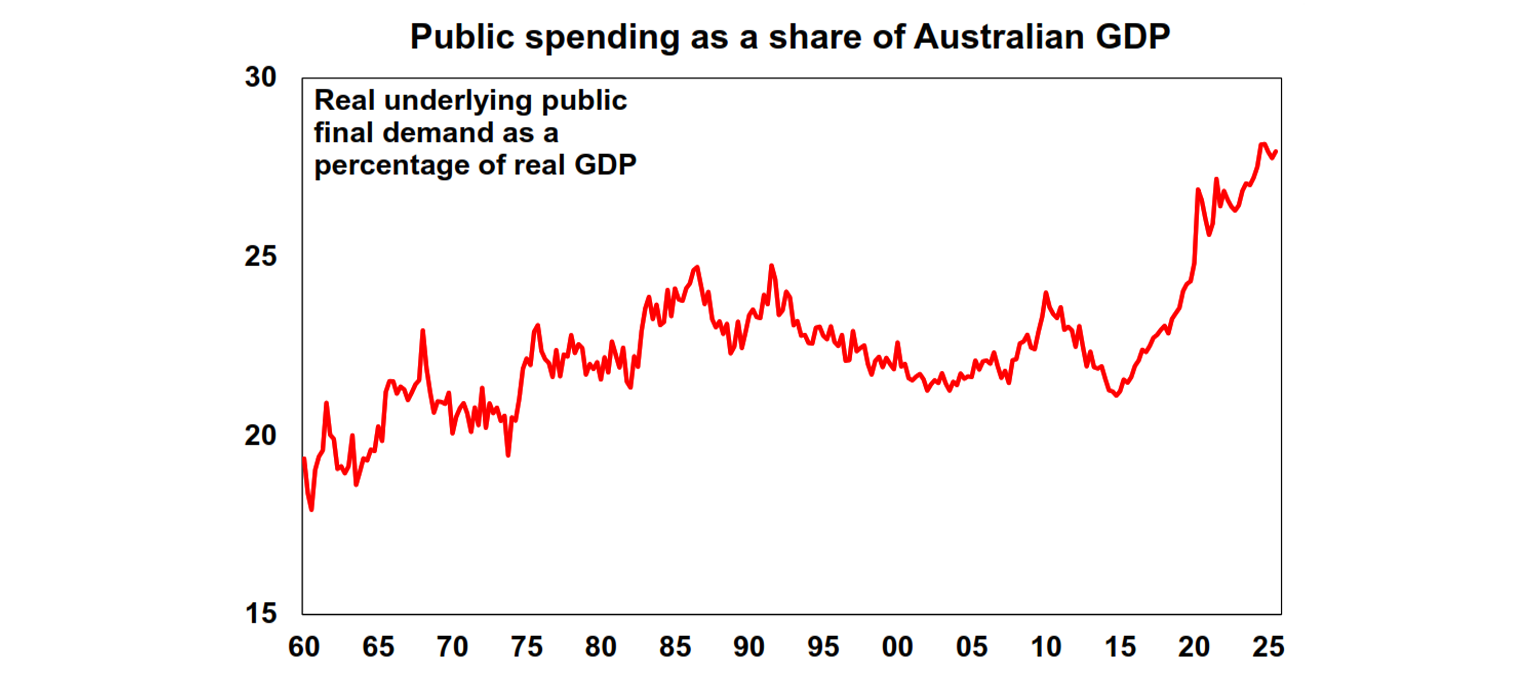

Second, and more fundamentally while public spending growth slowed to around 1.4%yoy in the September quarter, that followed many years of 4% plus growth which left public spending around a record 28% of GDP. As Governor Bullock noted, aggregate demand includes public and private spending. So high levels of public spending as a share of the economy are constraining the recovery in private spending that can occur without seeing the economy bump up against capacity constraints, which flows through to higher prices. So, the best thing that Australian governments can do to help bring down inflation would be to cut government spending back to more normal levels which would free up space for private sector growth without higher inflation. Lower public spending will also help boost productivity by freeing up resources for the more productive private sector which should help lower inflation longer term.

Source: ABS, AMP

The bottom line on rates

While the return to rate hikes on the back of inflation running above target is disappointing, I can understand the RBA’s desire to get back on top of it and avoid perceptions that its tolerant of high inflation. As they say “a stitch in time saves nine.” Looking forward we are confident that underlying inflation will continue to fall back to target and so see the RBA remaining on hold for the remainder of the year, even though the risks are on the upside. The best thing Federal and state governments can do is to quickly reduce the level of public spending to free up more space for private sector spending.

Implications for the economy and financial markets

For the economy the implications from the RBA’s rate hike with talk of more to come are as follows:

- Somewhat weaker economic growth from later this year.

- A bigger slowdown in home price growth – we were assuming home price growth this year of 5-7% but with rate hikes its possible we now see falls. Sure home prices rose in 2023 despite rate hikes but that was because immigration surged. Roughly speaking each 0.25% rise in mortgage rates knocks about $10,000 off how much a person on average earnings can borrow to buy (and hence pay for) a home.

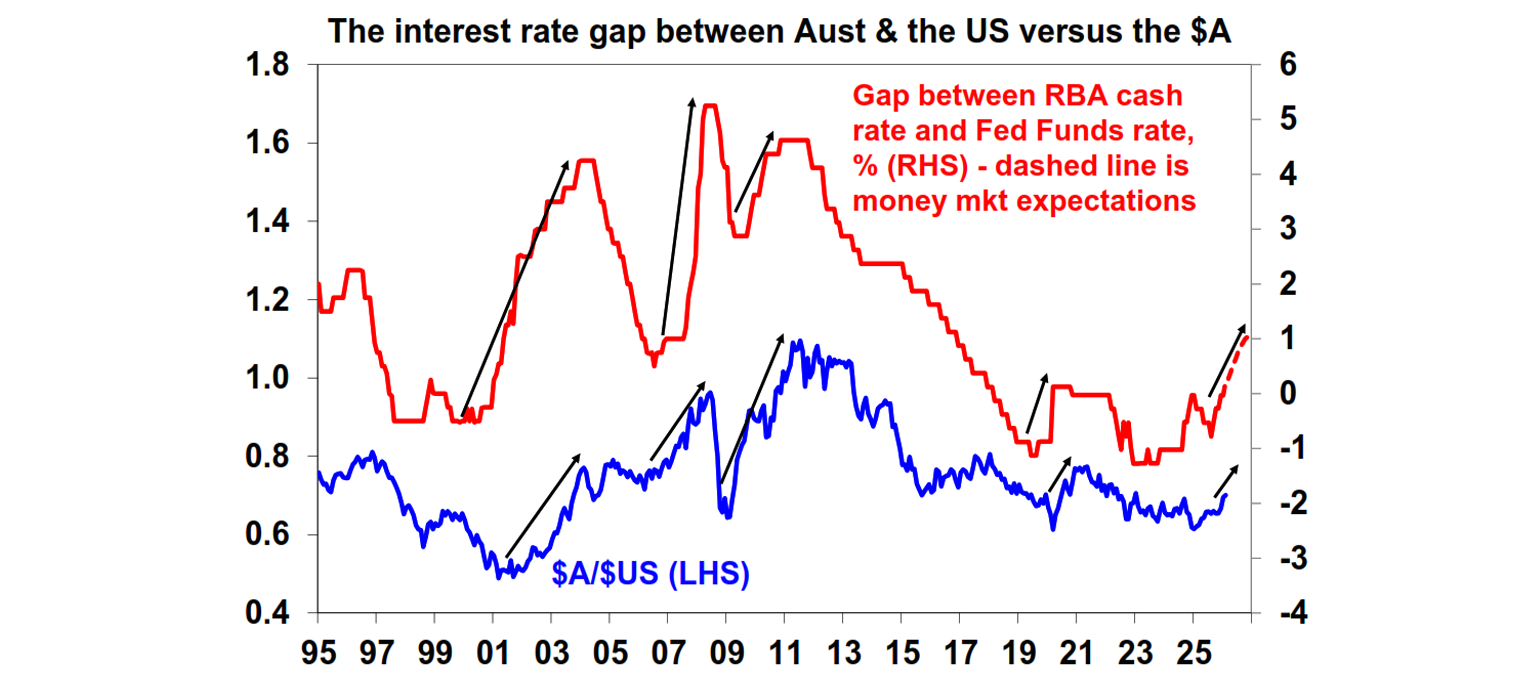

- The $A is likely to continue to rise as the gap between Australian and US interest rates widens further.

Source: Bloomberg, AMP

- All up this could have a dampening impact on the Australian share market’s relative performance this year although I still expect it to have a reasonable year as profits rise after three years of falls.